PB 11/11: Decision making for PMs - revisited

Why good decision lie at the heart of product management; and why rational decision making processes don't always work.

Going deep in decision making

A few weeks ago, I wrote about six steps for better faster product decisions. The feedback was really positive - and as a result, it’s an area I’m going to go quite a bit deeper on.

My (very sketchy) plan is to put it all together in some kind of only learning material before the end of the year. But let’s see how that goes

Over the next few weeks I’m going to pick up on a number of themes. This week it’s about why decision making is so critical to product management; and a look at the anatomy of a decision and why totally rational decision making doesn’t really work.

Good decisions: the heart of product management

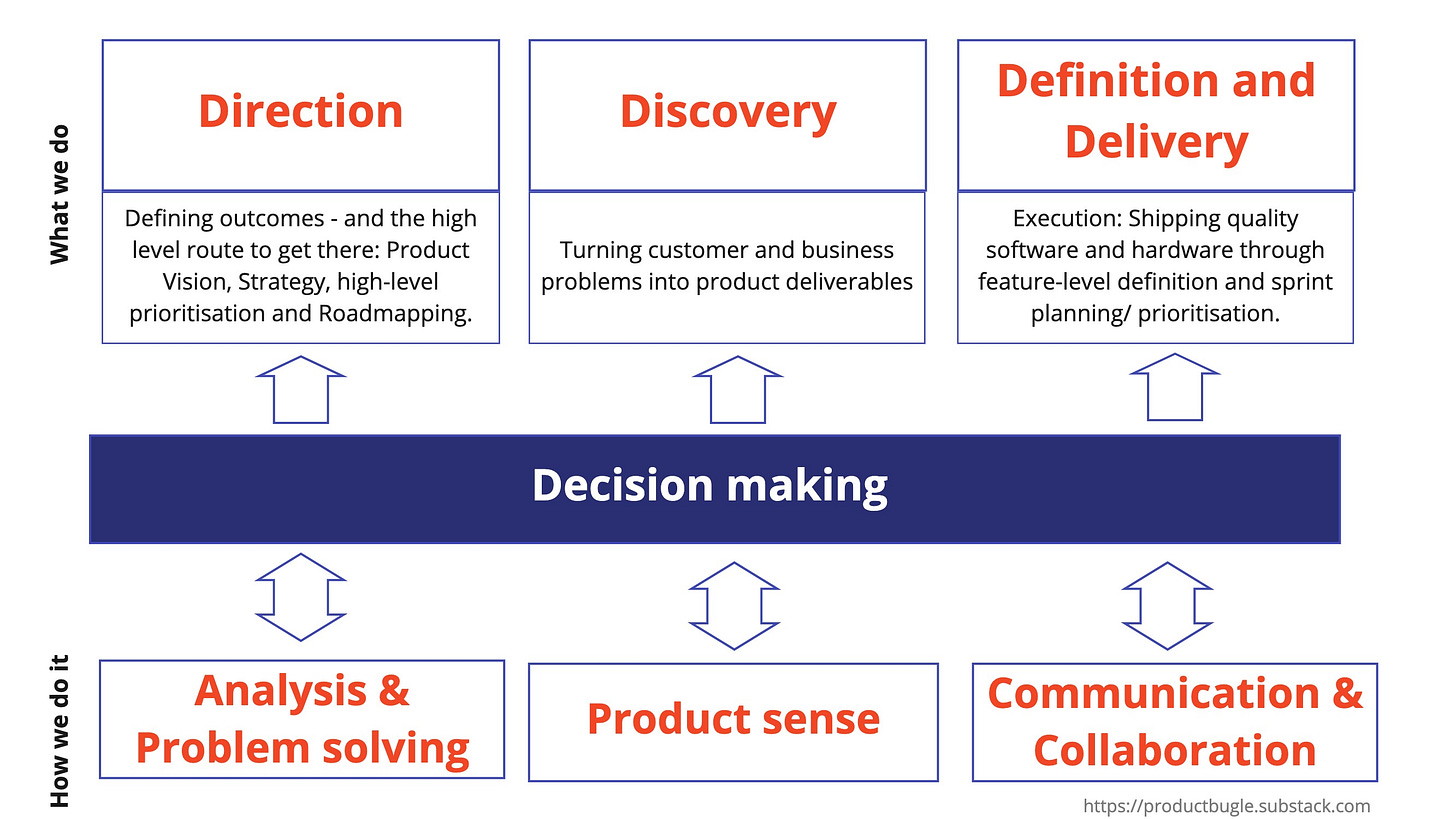

I did a slightly different version of this framework a few months ago - looking broadly at ‘what good product management looks like’. But as I’ve been digging into our decision making processes, it’s become achingly clear to me that no matter which functional product management task we’re taking on: from defining a strategy to the most granular of delivery calls - everything is fuelled by decisions.

If you’re a manager, this becomes even more true: as you have to make calls on who you hire and how you deploy them.

Overall the better decisions you make, the better software and hardware you will ultimately ship.

If you look at ‘how we work’ and the kind of skills we look for in product managers (the sort of things we should test for in interviews and assess in performance reviews) - these both drive and benefit from better decisions.

Analysis and problem solving: There’s a mutual loop between getting better at evaluating evidence and solving problems and the decisions we make. The better we get at one; the better we get at the other.

Product sense: Again a mutual loop. Product Sense is often presented as a sort of intuitive sense that can’t actually be coached. True - to a limit. Your intuitive sense can drive better decisions; but actually real product sense is what you build up through a feedback loop of having made countless decisions.

Communication and collaboration: Because so much of what we both have to communicate and work on with others is either making decisions or communicating decisions once they’ve been made effectively in order for them to become reality.

The anatomy of a rational decision

After my initial splurge on Decision Making I wanted to dive a bit more into some of the

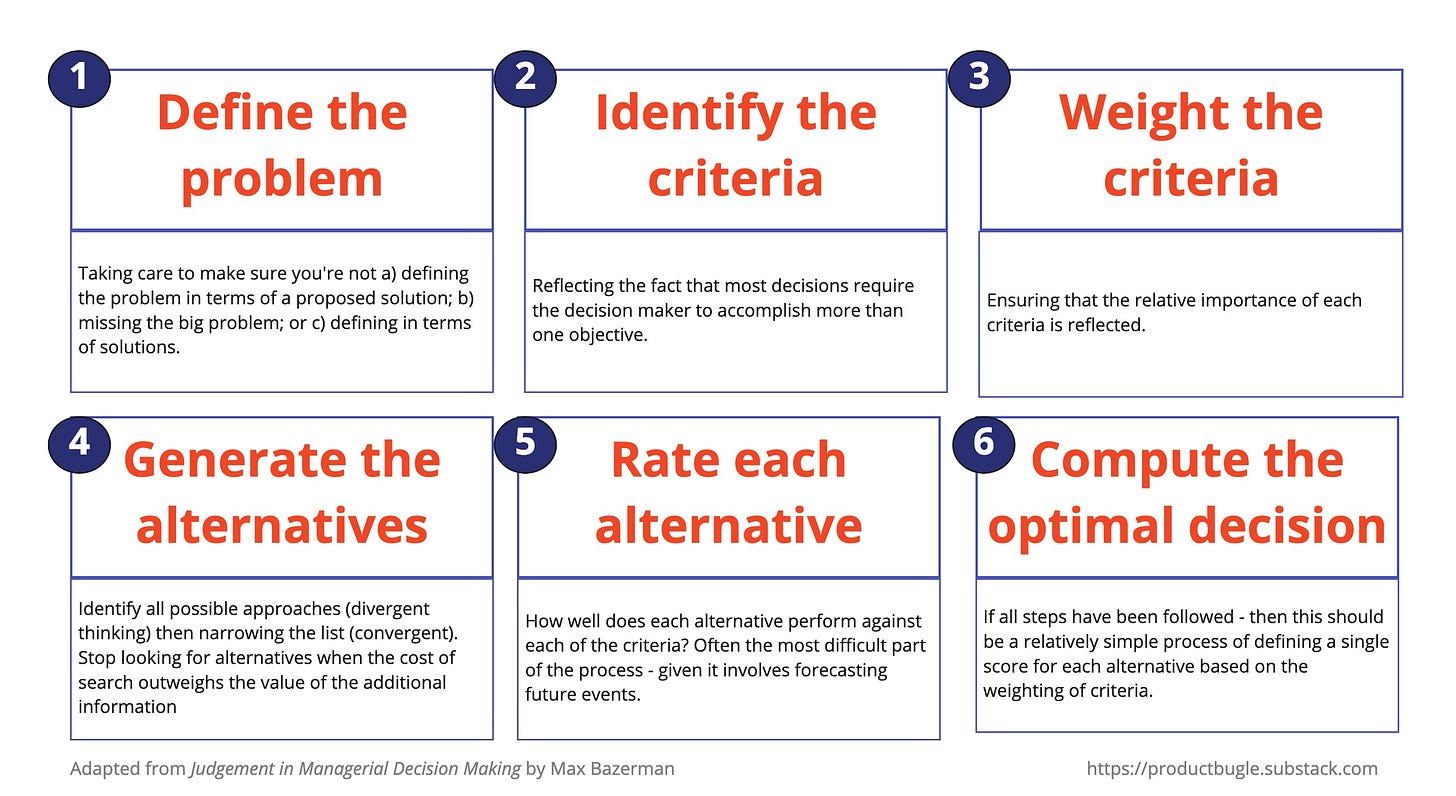

This framework is lifted from Judgement in Managerial Decision Making by Max Bazerman. It’s presented at the start of the book as ‘in an ideal world…this is how decisions would be made’: before the explaining over 200 pages why rational decision making doesn’t really happen.

In product land - this is pretty much how a score-based prioritisation framework such as R.I.C.E works.

This framework makes total and utter sense - and if it can be followed it should. But for product people (and lots of others) there are really three issues with it.

1. We’re not as rational as we’d like to think we are

It’s become pretty standard these days to talk about Behavioural Science when thinking about our products.

The general point is that people aren’t totally rational (ie: they don’t make decisions by making cold mathematical calculations), and when customers are say, going through a sign up funnel, they choices they make can be impacted heavily by how information is presented to them. [Just one article here - but you’ll find loads more with a quick bit of Googling].

Remarkably little however gets written or discussed about how we as product people aren’t entirely rational either; and just like those customers who can be swayed by how we present a set of options, our decision making is often flawed as a result.

Two very small examples

You launched a feature six months ago. It was meant to be used by 25% of customers. In fact it gets used by 5%. However, you had to deprioritise a fair bit of functionality along the way. You are now sprint planning and have to choose to either commit 1 week’s work to remove the feature; or 2 week’s work to add in 80% of the functionality you couldn’t do first time and see if this can get it to at least 20% usage. Which do you choose?

You are one of a number of Heads of Product leading teams of 4 - 6 PMs. You’ve noticed that a new recruit in another team hasn’t been performing well. Your strong hunch is that they’re not strong enough for the needs of the business. Their manager - a peer and friend of yours - comes to you and some of the other Heads, and says the new hire is coming to the end of their probation and he’s inclined to keep him. He acknowledges the new hire hasn’t had a great start, but it took ages to hire him and he believes he can be coached. He asks everyone to do a blind and anonymous ‘stay’ or ‘go’ vote. How do you vote?

These are essentially the same problem. The difference is really whether the initial decision was yours or not. If you chose to back the feature but vote ‘Go’ to the new hire. There’s a good chance you might have voted the opposite way if it was your predecessor’s feature and your hire. Even when the evidence is the same, we are much more inclined to ‘escalate’ (ie double down on a decision) when the original decision was ours.

We are also prone to dazzling optimism for our own decisions. Take the feature decision. Unless you made some spectacularly bad prioritisation decisions the chances of getting this from 5% to 20% are insanely slight. But if you’ve put in the time and the effort and you really believe in it - it’s very hard to see that.

With our friend’s hire. You can be objective. It’s an anonymous and blind vote, so you don’t have to worry about the social dimension. Your friend is sitting there wanting this person to work out, just as you want your feature to work out. Both because you’re not undoing a decision of your own; and because of the mechanism involved it’s much easier in this case for you to say no - and so you are more likely to do so.

Now imagine it’s your friend’s feature and you have a similar blind/ anonymous vote. Oh it’s so much easier to kill it now, isn’t it?

This is just one example of bias. At every point in that six step process there are opportunities for our personal biases and irrational thinking to get in the way.

We might frame a problem in such a way that it will ultimately skew towards a solution we already have in mind.

Our choice of selection criteria and their weighting might be biased by a particularly bruising meeting we just had about something vaguely related or a passing comment from your boss, but which isn’t objectively that important.

We might be blind to a number of alternatives - because we’re again clouded by some vaguely related recent experience; or because we’re too heavily invested in one of them.

Our scoring against different criteria is subject to all kinds of wreckless optimism and bias, especially if it’s done in a group setting (see below).

Even when we see the final calculation - if it’s not the result we want we might be tempted to go back and then skew the results to the one we wanted.

This, by the way, is one of the reasons where I’ve never felt that a precise scoring system such as R.I.C.E works when you have genuinely difficult and impactful prioritisation decisions to make. It gives a veneer of objectivity to an ocean of bias.

2. Other people: stakeholders, groups and politics

Mike Tyson isn’t much of a role model - but he has left us with one brilliant quote: ‘Everyone has a plan until they get a punch in the face’.

When it comes to decision making, that ‘punch in the face’ almost always comes from engaging with other people. Whether it’s customers, your boss, engineers, marketing, sales, whoever. At that point your carefully thought through rationale and beautifully structured thinking gets blown up as they see the world in a completely different way.

In an entirely rational world ‘what the boss thinks’ wouldn’t be one of your selection criteria. Because your boss would be totally rational too and capable of assessing the evidence in the same cool way as you. But too many managers think like Brian Clough, the famous football manager who, when asked what happens when he and a player disagree over something, said: ‘We sit down, and talk about it for 20 minutes. And then we decide I was right.’

The very nature of working in groups has an impact on the decision making process. There’s lots of research that diverse groups create more friction up front, but deliver better outcomes. Meanwhile groups of similar people thinking similar things will result in ‘groupthink’ - an unchallenging consensus that conveniently ignores evidence to the contrary.

Even when you have a diverse group, you can have inefficient meetings where load of opinions remain unexpressed because either everyone is hoping to line up behind the most senior person in the room; or someone who has a dissenting view simply doesn’t feel comfortable expressing it (similar to the case above about the new hire). Which is why the kind of rituals such as Dory and Pulse rituals they use at Coda are so critical.

I made one of my original steps for better decisions: ‘Involve the right people at the right time in the right way’ and I stick by that.

3. The need for feedback loops

This isn’t part of Bazerman’s book But it’s something that a lot of people pointed out when I first started on this topic. It’s also something I saw when I looked at decision making processes in medical situation.

Once a decision is made - you then need to capture the impact of it and feed that back into the system - either to iterate on the decision; or to provide a source of information for future decisions.

Decision making in an imperfect world

Bias exists. There are always going to be other people involved in your decision making. And even when you’ve made a decision on the most objective, rational criteria, there’s a chance you might have been wrong.

The point is - any decision making system has to be able to factor all of this in rather than wish it away. It’s as relevant if you’re a one-person product team in a three person start up; as one of a hundred PMs in a massive multinational.

The ‘rational’ decision model is a pretty good model as it happens. But as is so often the case with frameworks, it takes a combination of emotional intelligence, political nous, and hard-earned experience to adapt it in order to make it effective in your world.

Something I plan to cover next week..

Hi Simon, I'm trying to contact you for a journalism book I'm currently researching/writing. I wondered if you would be good enough to drop me an email at alleng3@cardiff.ac.uk so we can chat briefly? Thanks, Gavin Allen https://profiles.cardiff.ac.uk/staff/alleng3